S’porean Who Moved To China Returns Home To Be Portuguese Egg Tart Hawker

His flaky egg tarts are pretty delish.

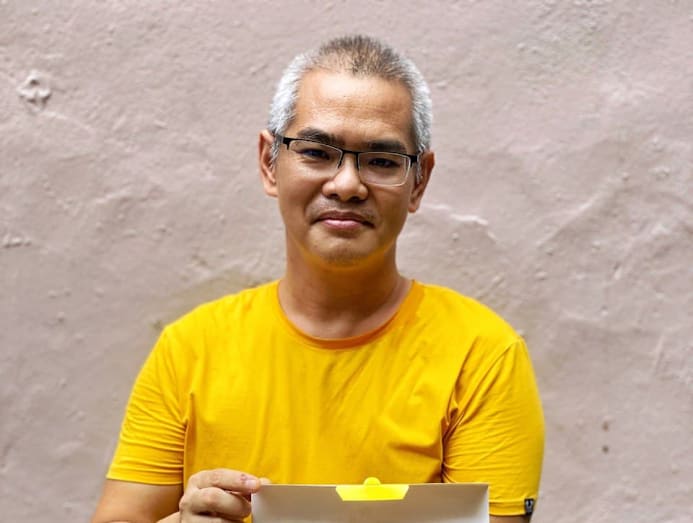

Robbie Liang, 47, was working as a mechanical production engineer in 2009 when he decided to quit his job and move to Yunnan, China. “I didn’t like the systematic style in Singapore. I couldn’t stick to that kind of life,” he tells 8days.sg.

China appealed to him as it shares cultural similarities with Singapore. Robbie later got hitched to his wife, who hails from Shandong, and the couple now has two kids — a son, 7, and a daughter, 6.

During their 12 years in Yunnan, they ran their own F&B business selling yogurt desserts, which Robbie identified as a market niche as the majority of the Chinese population has a genetic lactose intolerance towards fresh milk. “So they go for yogurt as a source of nutrients,” he explains.

Robbie’s wife, a baking enthusiast, also came up with a Portuguese egg tart recipe out of interest, and sold them as a “secondary product” alongside yogurt. Portuguese egg tarts (also known by its native name pastéis de nata), which originated in Lisbon and is also popular in former Portuguese colony Macau, are characterised by their crispy, flaky puff pastry crust and burnt egg custard filling that’s still creamy in the centre.

In 2019, husband-and-wife decided to close their yogurt business and move back to Singapore. “We came back for our kids’ education — they refused to speak to me in English because everyone around them was speaking Mandarin,” recalls Robbie.

Due to their F&B experience, they continued to work in the line by setting up another food business here. And this time, they focused on Portuguese Egg Tarts as Robbie points out there wasn’t much demand for yogurt in Singapore back in 2019. “Egg tart is a form of culture here too, since some of our ancestors are from China,” Robbie says. He notes that “Singaporeans are more used to Hong Kong-style cookie crust egg tarts”, but he decided to offer the flaky Portuguese tart as “I just love this type of crust”.

After being away from Singapore for 12 years, Robbie reckons he felt “totally new” when he first returned here. As he didn’t want to risk his family’s financial stability, he decided to “start at a slow pace” by opening a hawker stall instead of a standalone shop, which involves higher costs. “If I had opened a shop, I would probably have been bankrupt from this pandemic,” he muses. “Running a hawker stall is a good learning curve, and it was a blessing that I started small.”

He was also inspired by the movement to recognise local hawkers: “Singapore was bidding for our hawker culture to be included on the UNESCO [intangible cultural heritage] list back when I took over my stall in 2019.”

Robbie named his stall at Whampoa Drive Qinde (‘dearest’ in Chinese), as he says: “After being away from Singapore for so many years, only your dearest will work with you till you’re old.” Initially, he roped in his wife to help at the stall, but has since started working solo so she could become a full-time housewife. “With two kids, no way lah,” he laughs.

Being a hawker also requires patience and tenacity, as Robbie reflects: “You have to be mentally prepared to have no money for the first year. It takes time to build your pool of regulars. Other than that, I’m pretty happy with being a hawker.”

To tide his family through the first year after opening his stall, he relied on his kids’ Baby Bonus Child Development Account (CDA), which offers a cash gift to help Singaporean parents with the costs of raising their children.

Robbie now personally makes and sells at least 300 egg tarts on weekdays, and “more on weekends”. As his stall sells only takeaway egg tarts, his business has managed to stay afloat through the Circuit Breaker last year and the two rounds of Phase 2 (Heightened Alert).

Qinde’s signboard also advertises “traditional waffles and other pastries” like cheesecakes and brownies, but Robbie says he is now selling only egg tarts as “the demand is already there” and he has no capacity to offer more menu items. “I do everything alone to save on manpower costs, so there’s less [financial] risk during the pandemic. You can try to do more and get the money, but you’ll end up with no life,” he observes drily.

Despite selling Portuguese egg tarts, Robbie says he markets his wares only as generic egg tarts. “I won’t say my tarts are the Portuguese type. It might offend those from Portugal! (Laughs) I didn’t try any egg tarts from Macau or Portugal at all. The recipe just came from my wife, and I think it tastes good and started selling it. Simple as that,” he says. “There’s no such thing as authenticity. Just as long as it’s nice!”

To cater to the older residents living around his Whampoa stall, he also modified his egg custard recipe to be less sweet. Robbie hopes to eventually expand his business and open more outlets, but admits that he has to monitor the pandemic situation first. “If you’re not cash rich, don’t expand [hastily]. I have a family to take care of,” he says.

Robbie’s petite egg tarts, which are packed in a flat paper box, look appealing at first sight. Layers of flaky puff pastry encircle each tart, cradling its crown jewel of egg custard baked to a golden-brown finish.

The egg tart is pretty delish; we enjoy the delicately crispy crust that crackles to the bite, balanced with smooth, eggy custard that melts on our tongue. Our only bugbear is the faintly greasy, artificial flavour of margarine that accompanies each bite; those who have no beef with margarine will find this nonetheless enjoyable.