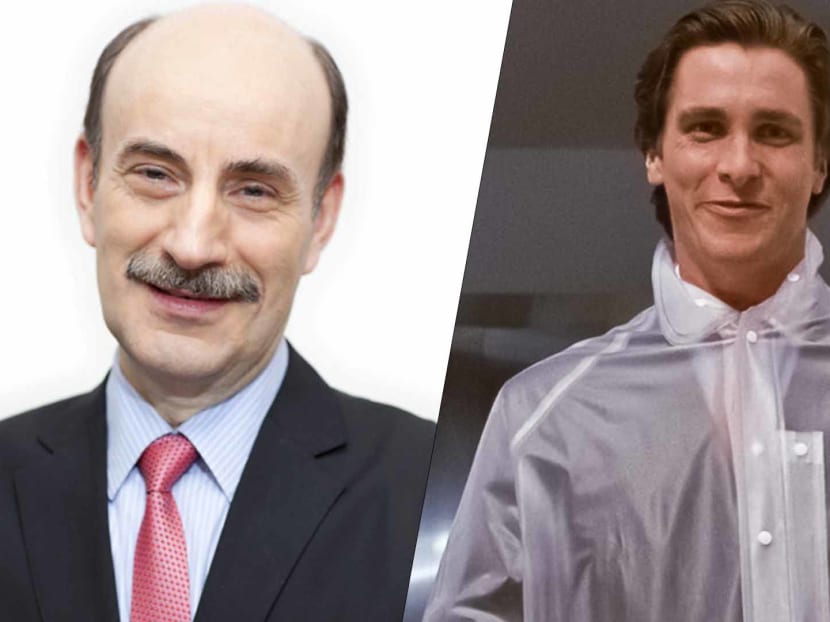

Talking Movies' Tom Brook Once Shared A BBC Office With A Colleague Who Went On To Direct Christian Bale In American Psycho

The BBC turns 100!

To mark the occasion, Tom Brook, the presenter of Talking Movies, the BBC’s long-running film programme, sat down with five filmmakers who started their careers with the broadcaster.

Two-time Palm d’Or winner Ken Loach cut his teeth with BBC directing TV dramas in the 1960s, while the iconoclastic Mike Leigh did time directing BBC’s Play for Today anthology series in the 1970s. James Marsh, the Oscar-feted helmer of Man on Wire, built his early CV with BBC documentaries.

Mary Harron, the Canadian auteur of American Psycho, worked as a journalist, critic and presenter of the BBC’s The Late Show in the 1990s. (Fun fact: Brook worked on that show too, and they even shared the same office.)

Sally El Hosaini, the Welsh-Egyptian filmmaker whose The Swimmers, a true-life story of two refugees from Syria who competed at the 2016 Rio Olympics, was raised on BBC World Service Radio and worked as a script editor and production coordinator on indie documentaries.

While discussing the BBC’s impact on the filmmakers’ careers, Brook, 69, also weighed in on his own relationship with the corporation, which began in 1976 when he first joined as a news trainee.

“I was a phone phreak,” the New York-based Brook tells 8days.sg over Zoom. “You might not know what that means, but it was like an early version of being a computer hacker,” he says, with a laugh.

“I think that explains my fascination [with the news],” says Brook, who’s been with Talking Movies since 1999. “I wanted to escape from the world in which I lived. I found that by dialing all these numbers — we lived in a town north of London — I could dial basically all over the world for the price of a local phone call. And that opened up a new world for me. And the BBC was like that for me. I remember going to sleep when I was very young, we had this huge old radio.

“When I say huge, it was about three or four feet high and I’d put it next to the bed. I heard a medley, the sounds, the voices, which emanated from London, telling me about a world filled with wonder, hope, and promise. I think that really spurred me into wanting to work for the BBC because it was this kind of amazing communications distribution network as well as a place that created a lot of interesting content."

Here, Brook shares more stories about his time with the BBC.

8 DAYS: The BBC turns 100! As you were interviewing the filmmakers for a series of BBC Centenary Specials, did you also reflect on your time with the broadcaster?

TOM BROOK: When I interviewed five key filmmakers who’ve had an impact on the film industry, I was mindful of the BBC is a hundred years old, and it made me think about my own involvement [with the broadcaster]. I began training with the BBC in 1976, which is a pretty long time ago. Through the BBC, I got an excellent training in news journalism. They had the News Training Course, and they trained you in all aspects of broadcast journalism as it existed with the technology that was prevalent at the time. So I worked in radio and, and television in London and newsrooms and also around the UK and it was a very good training.

I worked in Birmingham, Manchester, and then in Belfast for quite a long time during the sectarian troubles. So I learned a lot of skills of news reporting, and I think that if you can somehow get it right with news reporting, it is the key to everything. I think news reporting can prepare you to be any kind of journalist really, or even a documentary filmmaker. Not that I’ve really done much of that, but, you know, it's all about learning how to organise material, put it in order, get a story, and portray it in hopefully interesting ways. So, yeah, I’ve had such a good experience with the BBC and had such a good training, it really couldn’t have been better.

How is your work perceived by colleagues who cover hard news?

It's interesting because people who work in news tend to think of reporting on arts culture or film as being a ‘soft’ option, not something that real journalists do (laughs). Um, and it’s odd because even though they may have that attitude, they’re always very curious about what I’m doing and they want to know about it and everything. So I don’t know why that is. I think it’s changed. I think when I began in the late ’70s, there was a kind of like an alpha male view of doing news and that anything else was considered outside of that orbit to be a soft option and not really worthy of serious journalistic treatment. But I think it has changed and people realise that you can cover the film industry or really any aspect of the entertainment industry with the normal practices of journalism in a way that’s not just [doing puff pieces for publicists].

Looking back at your training, what do you think young journalists today lack?

I think journalism nowadays is all over the place. You know, it's been diluted in a way. A lot of it is digital or online. Maybe the art of storytelling has got lost a little bit — you really do need to have a narrative. I sometimes watch a younger colleague beginning to edit a video store and I said, “Oh Lord, where are they going with this?” You know, they just bring all the images together, bits of audio — they have a very different approach. But having said that, you know, what they end up with sometimes can be maybe just as good as what I would do using traditional storytelling. The other thing is that the whole structure of journalism and work practice has changed over the last 40 or 50 years. Maybe this is because I’m an old man now, but I think with younger people, there is a sense of getting the job that they want very rapidly. And it doesn't always happen that way. Whereas when I was young, you had to do a long apprenticeship before you got anywhere. But, you know, I mean, I think that’s not just true of journalism, it's in every aspect of working life.

Let’s chat: Tom Brook with Mike Leigh, one of the BBC alums-turned-filmmakers featured on Talking Movies’ series of BBC Centenary Specials.

What do you make of Tik Tok? We are pivoting to that kind of reporting.

I was under tremendous pressure from my [boss to do that as well]. I think because of my age — I'll be 70 next year — there is a generational issue so social media is not something that comes naturally to me. I have to really work at it and they keep wanting me to do Twitter. And I found it a pain in the neck, to be honest with you, because one thing about Twitter, I feel, it has a kind of self-referential nature to it. “Here I am, look at me, look at me here”. I mean, it’s calling attention to yourself. I think, if you can be bringing attention to something that has value, you know, by way of meaningful thought or something to do with the human condition, that’s all well and good.

How has BBC changed over the years in terms of nurturing filmmakers?

If you speak to veterans like Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, they felt very supported by the BBC in the early days. They worked on BBC dramas in the 1960s and 1970s and did really interesting work, often dealing with controversial issues. And they felt they had the full backing of the BBC. Speaking to Mike Leigh, he feels that the BBC, in terms of [dramatic content], is less adventurous now and too politically correct. I think he may be feeling a little bitter because he recently pitched the BBC a project and it got turned out. But I think it’s fair to say that in the 1960s and seventies, the BBC, in terms of drama and training, was behind people who eventually became feature filmmakers, was a very exciting and free-spirited and daring place, actually. There isn’t so much of an infrastructure now to develop the talents of British filmmakers. But there are so many people, like Kenneth Branagh, who had his first directing job at the BBC in Belfast. The British film industry has really been helped by the BBC. I think it’s known but it’s not often discussed as much.

In one BBC Centenary Special, you spoke to Mary Harron, the director of American Psycho, with whom you once shared a BBC office. You both were working on The Late Show, BBC’s long-running arts magazine show. I’m wondering: When she was making American Psycho years later, did she ever let you in on the behind-the-scenes drama? It’s well-documented that the producers wanted Leonardo DiCaprio, not Christian Bale, for the Patrick Bateman role.

Well, actually, you see, the thing is she used to come to the New York office, this was 30 years ago, probably 10 years before she made American Psycho. I was always somewhat in awe of her because she seemed very talented. You know, I would do these stories for The Late Show, which would, you know, they were okay, but they were pedestrian. But she would make them as if they were minor feature films, They'd be very elaborate productions. I didn’t have an inkling about her interest in that material. Her first film, I Shot Andy Warhol, is about radical feminist Valerie Solanas. I do remember her being interested in that part of the downtown New York scene in the 1980s. It was interesting when I went up to see her the other day — she lived in upper Manhattan now — and that seems like such a different world. And she's a mother. I met her, and one of her daughters. It was nice to see her, but I didn't know anything about American Psycho. I don’t know if she did at that point.

Catch Talking Movies’ BBC Centenary Specials on BBC World (StarHub Ch 701) on Sun (Oct 23), 10.30pm and Mon (Oct 24), 4.30am.The Swimmers drops on Netflix on Nov 23.

Photos: BBC World News, TPG News/Click Photos